|

|||||||||||||||||||||

TEAMSTERS

AND TURTLES, HACKERS AND TIGERS

DeeDee Halleck

> Cyber Activism & the Independents

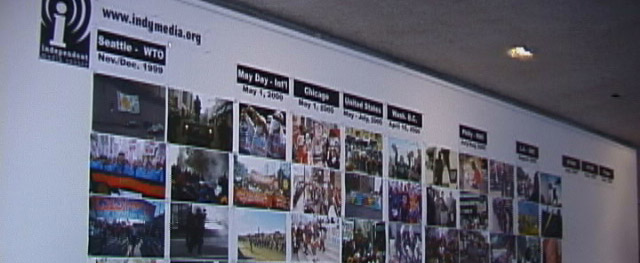

From

Seattle to Davos - and D.C., Prague, Calgary and Windsor - media activists,

environmentalists, tree huggers and labor rank and file have coalesced

into a formidable force that has not only had an impact on the international

money lenders, but has also caused major trouble for corporate giants

such as Monsanto, Gap and Nike. On the lam, Monsanto is changing its name

and trying to spin off agriculture.

As

the global movement for justice and accountability arose to counter corporate

globalization, there was finally a recognition by progressive groups of

the importance of alternative media and the realization that the information/

entertainment oligarchy is at the forefront of global capital. The anti-globalization

movement sees clearly that corporate media is an integral part of the

problem. For these activists, creating new ways of communicating must

be part of the solution. Media activists have constructed their own public

information spaces by integrating various media formats and technologies:

camcorders, Web radio, streaming video, microradio, digital photography,

community cable access, DBS (direct broadcast satellite) transponders

and laptop journalism. The revolution is not only televised, but digitized

and streamed. This is not an attempt to "get on TV" but a commitment

to create new forms of information sharing using new spaces and technologies

and new ways of collaboration. The movement for an alternative media,

with its flexible and open structure, its democratic rendering of the

use-values of new technologies, and its continual involvement in interconnecting

people in a transnational movement, provides an model of the evolution

of a radical opposition, from the spontaneous appearance of individual

creative practice, to the collective gathering of small co-operatives

with enhancement of practical and technical skill, and to the growth of

national and international collectives.

The

following is the statement of purpose of the Boston

Independent Media Center, created in less than two weeks in response

to a global bio-engineering conference held in Massachusetts last winter.

This statement has been taken up and tweaked or supplemented by several

of the independent media centers, most recently in Windsor,

Ontario. "The Boston Independent Media Center is a collectively run

media outlet for the creation of radical, objective and passionate tellings

of the truth. We work out of a love and inspiration for people who continue

to work for a better world, despite corporate media's distortions and

unwillingness to cover the efforts to free humanity. Indymedia provides

resources and infrastructure for activists, citizens, communities and

groups to tell their stories."

Behind the strategic blockades by the radical environmentalists and the lively and passionate video tapes, pirate radio shows and Web sites produced by the camcorder-commandos and server jocks, is an authentic revolution: a revolution in the form of public action and its documentation. The most radical aspect of this new movement is its non-hierarchical nature. The decision making is by consensus. All participants are themselves empowered.

The collaborative nature of the Indymedia work is something the mainstream press can't fathom. In covering this media revolution, the corporate press, either unwilling or unable to see the implications of this new form of information sharing, has focused on trying to find evidence of "hacking". Hacking is something the main stream reporters can deal with. The more complex forms of anti-global cyber activism they can't appreciate. They are stuck with the notion of a sort of individual geek working as maverick computer terrorist and they have a hard time "getting" decentralized consensus based media affinity groups.

The Independent Media Centers have emerged as models, not only for new ways of media making, but as practical examples of collective production. Many different streams came together: the video activist community, the micro-radio pirates, the computer hacker/codewriters, the 'zine makers and the punk music world. From the beginning there has been a committment to democratic process on all levels within the IMCs. Decision making procedures are discussed frequently on IMC list serves. Though quite popular and visited by literally millions, the indymedia websites are not about spectacle, but about involvement, engagement and participation. The front page is divided into columns, the first being links to all the IMC websites from the various locations through out the world. The center section is a loosely edited, regularly up-dated, news post. The right hand column is for on-going continual posting open to all.

The

process of Indymedia is completely open, and completely accountable: there

is no gate keeping, no selection process (except for what is selected

for emphasis on the center news column). Any statement is immediately

available for comment, discussion and/or correction. This open structure

is especially appropriate for the type of movement which has evolved around

globalization. As "J.M.G." pointed out during the demonstrations

in Melbourne at the September 2000 meeting of the World Economic Forum:

"The inabilities of the mainstream media to comprehensively document

the issues and events surrounding S11 are contrasted by the growing number

of community based, independent media outlets and individuals granted

a forum for interactive dialogue through IndyMedia. The IndyMedia site

provides a 'channel' for open discourse, free of editorial, as a simple

click on the 'publish' button enables anyone and everyone to upload their

stories. Rather than challenging or infiltrating the mainstream the objective

of IndyMedia is to create a system outside of the dominant socio-political

culture, empowering citizens by providing greater access and opportunity.

Under this method of communication the traditional concept of the 'audience'

is refuted - challenging the reader/writer to come to their own conclusions

by wading through the diverse range of stories relating to s11 and other

events. The sheer enormity and breadth of information available has lead

to a greater level of engagement with both the issues and the other reader/writers.

Creating this space for audience control has harnessed the inherent qualities

of hypertext - unlike the majority of on-line news services, which remain

overwhelmingly one-way in their transmission."

> The Public Broadcasting Fortress

And

where is public television in all of this? Public television's participation

in these global discussions is pretty much limited to promotional advertisements

for Archer-Daniels-Midland, Miracle Gro, Amgen and other agro-businesses.

As it's presently constituted, public television is incapable of almost

any kind of reporting on the sort of systemic critique that this global

movement represents. We have a nominally public communication apparatus

that is structurally imbedded in the corporate system. Any sustained critique

of that system cannot take place within that apparatus.

Public broadcasting sees itself as an adversary to independent production.

One of the most distressing signs of this was the way in which NPR (National

Public Radio) has gone to bat against microradio. Even the National Association

of Broadcasters has not been as smarmy as the lobbyists for so-called

public broadcasting in getting Congressional passage of anti-microradio

legislation.

In

terms of video production, PBS stations have set themselves up as fortresses

against not only independent producers but community groups of any stripe,

except perhaps the Junior League or the chambers of commerce. What a contrast

there is between the icy gloom of most publicly funded PBS station offices

and the bustle and excitement of the many successful cable access centers.

There community organizations feel welcome; there independent producers

can utilize resources and channel space. Shouldn't public television also

be a space in which the community participates?

During

the late 1970's the second Carnegie Commission sparked an occasion for

activity in the critique and reform of public television. I was involved

in the movement as a representative of the independent media community,

as President of the Association

of Independent Video and Filmmakers (AIVF). There was an impressive

coalition of media producers, labor, women's organizations, civil rights

activists, progressive religious organizations and others who came together

to appeal first to the commission and then directly to Congress to take

the need for an authentic public television seriously. And gains were

made; there was an acknowledgement of the work of independent producers

and legislation for affirmative action at stations and in programming.

On some level, perhaps we can thank this movement for the few courageous

series that PBS has created: "Matters of Life and Death," "POV"

(Marc Weiss, founder of POV,

was a veteran of that '70s struggle) and, indirectly, but certainly part

of the picture, "Eyes on the Prize." And wasn't it right after

this activism that Charlayne Hunter Gault joined Jim and Robert?

The

most far-reaching result of this organizing effort perhaps has been the

implementation of "Sunshine Laws" on a national scale. These

right-to-know laws have been won in California thanks to the efforts of

Larry Hall, Henry Kroll and other Bay Area activists. The laws mandate

that organizations which receive funds from the Corporation

for Public Broadcasting (CPB) must hold open board meetings (and committee

meetings, except for those portions of the meetings which deal with personnel

issues). This law is one that the Pacifica

Foundation has consistently violated (though CPB itself has to enforce

the regulation and, in the case of Pacifica, has been reluctant to do

so), and it is routinely ignored by many stations around the country.

However, as far as I know it is still a law, and if citizens get organized,

this is quite an important tool for community groups to have at their

disposal.

There

is no Carnegie Commission at this time to focus a critique. Public television

as it is now constituted would be too vulnerable, too open to criticism.

Labor is too militant. As Seattle has demonstrated, progressive forces

are too organized. So there has been no national forum for that sort of

discussion. However, there is a deep need for a new assessment, and I

hope that the recent "Public

Broadcasting and the Public Interest" conference, as far as I

know the first of its kind, is the beginning of a new movement to assess

public broadcasting and to reinsert the public-interest mandate that was

the impetus for its beginning

>

A new reform movement

A

reform movement for this new millennium has resources which were not present

in the 1970's. Things are different now. The enthusiasm which coalesced

around the Media and Democracy Congresses in New York (1996) and San Francisco

(1997) are an indication of the potential for progress. There is potential

for a broad movement for communication reform. Aside from the impressive

and enthusiastic Independent

Media Centers (IMCs), I will enumerate a few of the other assets now

in place for reinvigorated media activism:

1. Academic Study

The

serious, sustained research that is being done on the public sphere and

in cultural studies at many universities. By framing the discussion of

public television in terms of the privatization of public space and the

need for an authentic public sphere, critical theory has given the reform

movement a wider perspective. By showing the historic consequences of

colonialism, slavery and academic elitism, the cultural studies movement

has made diversity not only a required college class, but a requirement

for cultural administration at any level.

2. FAIR

The

on-going work of Fairness

and Accuracy in Reporting, whose publications and archives provide

potential reformers with ammunition and examples. Their crucial

studies of the commercialization

of children's programming, of the recurring bias on "NewsHour"

and the lack of working-class representation on PBS and NPR are landmark

studies which give substance to public broadcasting critiques.

3. Activists Using Media

The

wide use of television and computer media as activist tools within the

environmental, labor and social-justice movements. Years ago it was hard

to convince a rank-and-file union group that they needed a video about

their cause. Now it is an accepted necessity. The United

Farm Workers were pioneers in this endeavor with their emotional look

at pesticides in the short tape, "The Wrath of Grapes." That

tape has been reproduced more than a million times and continues to inform

struggles around pesticides. "Lock

Down USA," produced by Deep

Dish TV, is virtually a part of the Schools

Not Jails movement and is being shown in literally thousands of high

schools and colleges. These examples are not films about the movement

or films about a subject which the movement also addresses, they are part

of the movement.

4. Media Literacy

The

expanding base of media education and the media literacy movement which

has adherents in almost every public elementary, junior and high school

in this country. Teachers are realizing that they need to make the media

a subject for discussion, even as early as kindergarten. And not only

discussion, but also practice. With the demise of art-education funds,

teachers often must bring their own personal camcorders to school, but

for many of them, filmmaking has become a useful catalyst for creative

work by groups of students. For some the video camera becomes a tool for

educational research within their communities. One example is Fred Isseks

of Middletown, New York, whose students have documented

the corruption and dangers of the town dump - to such a degree that the

landfill mafia has made threats on the teacher's life. But their work

resulted in a major investigation of the problem and has (at least for

now) put an end to a long-standing practice of allowing the dump to be

used for extremely toxic waste. The teachers and students of these classes

know the potential for educational television.

5. Coalitions and Web Sites

The

Citizens for Independent

Public Broadcasting, the Center

for Media Education and People

for Better TV form a useful band of infrastructure support for future

reform initiatives. There are useful and informative Web sites such as

Nettime, Alternet

and MediaChannel,

which regularly discuss communication policy issues. And the Media

Access Project, a veteran center of public-interest advocacy, is still

there.

6. Public Access TV

Public

access television is one of the most exciting and controversial U.S. media

developments within the past two decades. In 1972 the Federal Communications

Commission (FCC) mandated that cable systems be required to provide channels

for public access. Many regularly scheduled television programs have been

made for local networks, some of which have been running for over ten

years. The subjects can range from astrology, call-in shows to discussions

of spousal abuse. In the United States, the numbers of public channels

and extent of equipment and facilities available are negotiated by the

cable corporation and the local governments in the process of franchising.

This process can be quite complex and can take several years to finalise.

The structures resulting from the negotiations, known as 'access' or 'PEG'

(public, educational and governmental) channels have created an informal

network of non-commercial makers and viewers in several thousand cities

and towns in the United States who have had to inform themselves about

the political economy of corporate media in very concrete ways as they

battle for just cable franchises. They have created new forms of public

communication participation. In both the form of their governing bodies

and the formats of their interactive programming, many of the community

television centers are models of what an authentic television space for

and by the public might be.

7. FreeSpeech TV

Freespeech

TV is a publicly-supported, independent, non-profit TV founded in

1995. In 2000, FSTV realized its goal of launching the first national

progressive, non-commercial television network when it was awarded a full-time

satellite channel on DISH Network as a result of an FCC policy to set

aside 4%-7% of satellite channels for public interest channels. This set-aside,

which has become part of the direct broadcast rules, was itself proposed,

lobbied and fought for by Freespeech TV. It is now available nationally,

24/7, on DISH Satellite Network. Deep Dish is a model of how satellite

technology can create networks of interest. By organising the programming

around issues from many different geographical sources, the network re-connects

often scattered and isolated movements. By identifying producers and groups

from around the country, Deep Dish uses video to create community, to

bring people together who might not know about each other. Freespeech

will be working with Deep Dish, the IMCs and hundreds of independent producers

to provide an authentic alternative to public television as it is now

constituted. The success of this effort may very well impact PBS.

8. International Reform

And, finally, there is the international community. Back in the 1970's the movement to reform public broadcasting was informed and supported by an international movement for a "new world information order." The MacBride Commission was in full swing, and there were research papers and symposia addressing issues of media democracy. That commission is one of the principle reasons the United States still has not paid its share of United Nations dues (in the billions). At this point, although there is no international organized movement for information parity, there is a growing realization that the rapid privatization of public space - such as we've seen in Eastern Europe - was a mistake. There is growing outrage against the violence and exploitative nature of commercial media and global consumer capitalism. The global movement for empowerment and accountability, which has been made manifest in the struggle against the WTO and the IMF, sees culture as absolutely imbedded in the domination and exploitation it is fighting. It will ultimately have an impact on broadcasting structures not just in the world, but here in the States - the belly of the beast - and certainly, eventually, at PBS itself.

This

article was adapted from a paper on PBS presented at the "Public

Broadcasting and the Public Interest" conference, University

of Maine, June, 2000 and a second paper on the Indymedia network presented

at the "Our Media"

preconference in Barcelona, July, 2002.